On 12 August 1765, the Mughal emperor appointed the East India Company as the Diwan of Bengal. As Diwan, the Company became the chief financial administrator of the territory under its control. The company had to find a way to manage the land and its revenue so they could make enough money to cover their increasing costs. They also needed to make sure they could buy and sell the products they wanted as a trading company.

Revenue for the Company

The Company had become the Diwan, but it still saw itself primarily as a trader. It wanted a large revenue income but was unwilling to set up any regular system of assessment and collection. The effort was to increase the revenue as much as it could and buy fine cotton and silk cloth as cheaply as possible.

Within five years, the value of goods bought by the company in Bengal doubled. Before 1765, the Company had purchased goods in India by importing gold and silver from Britain. Now, the revenue collected in Bengal could finance the purchase of goods for export.

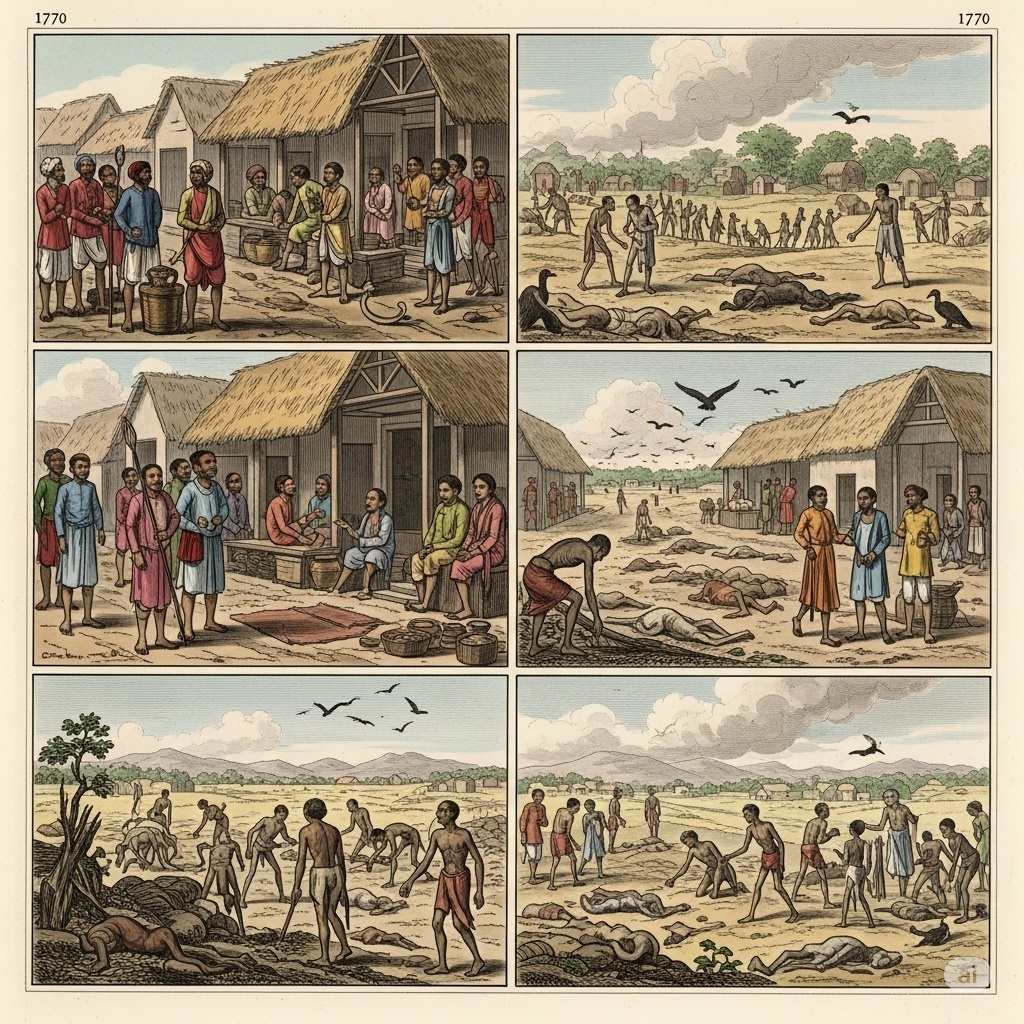

Soon, the Bengal economy was facing a deep crisis as the artisans were deserting villages since they were being forced to sell their goods to the company at low prices. Peasants were unable to pay the dues that were demanded from them. Artisan production was in decline, and agricultural cultivation showed signs of collapse.

Then, in 1770, a terrible famine killed 10 million people in Bengal. About one-third of the population was wiped out.

Need to improve Agriculture

The company officials began to feel that investment in land had to be encouraged and agriculture had to be improved. The company, after two debates on this issue, finally introduced the Permanent Settlement in 1793.

Land tenure is the system of land ownership and management.

Land System in India related to: Who owns the land? Who cultivates the land? Who is responsible for paying the land taxes to the government?

Three types of land tenure systems existed in India before Independence. They are: Zamindari System, Mahalwari System, Ryotwari System

Zamindari System or the Landlord-Tenant System

The Landlord-Tenant or Zamindari system was created by the British East India Company in 1793 by Lord Cornwallis by the Permanent Settlement Act. By the terms of the settlement, the rajas and taluqdars were recognised as Zamindars.

Under the Zamindari System, the Zamindar was declared the owner of the land and was responsible for paying the land revenue to the company. The

The share of the government was fixed at 10/11th, the balance going to the Zamindars as remuneration. The amount to be paid was fixed permanently, that is, it was not to be increased ever in future. It was felt that this would ensure a regular flow of revenue into the company’s coffers and, at the same time, encourage the zamindars to invest in improving the land.

Since the revenue demand of the state would not be increased, the zamindar would benefit from increased production from the land.

The Problem with the Zamindari System

The permanent settlement created problems. Company officials soon discovered that the zamindars were, in fact, not investing in the improvement of land. The revenue that had been fixed was so high that the zamindars found it difficult to pay. Anyone who failed to pay the revenue lost their zamindari rights.

Numerous zamindaris were sold off at auctions organised by the company. By the first decade of the 19th century, the situation changed. The prices in the market rose, and cultivation slowly expanded. This meant an increase in the income of the zamindars but no gain for the company since it could not increase the revenue demand that had been fixed permanently.

Even the zamindars did not have an interest in improving the land. Some had lost their lands in the earlier years of the settlement. Other zamindars now saw the possibility of earning without the trouble and risk of investment. As long as the zamindars could give out the land to tenants and get rent, they were not interested in improving the land.

Problems for the Farmer due to the Zamindari System

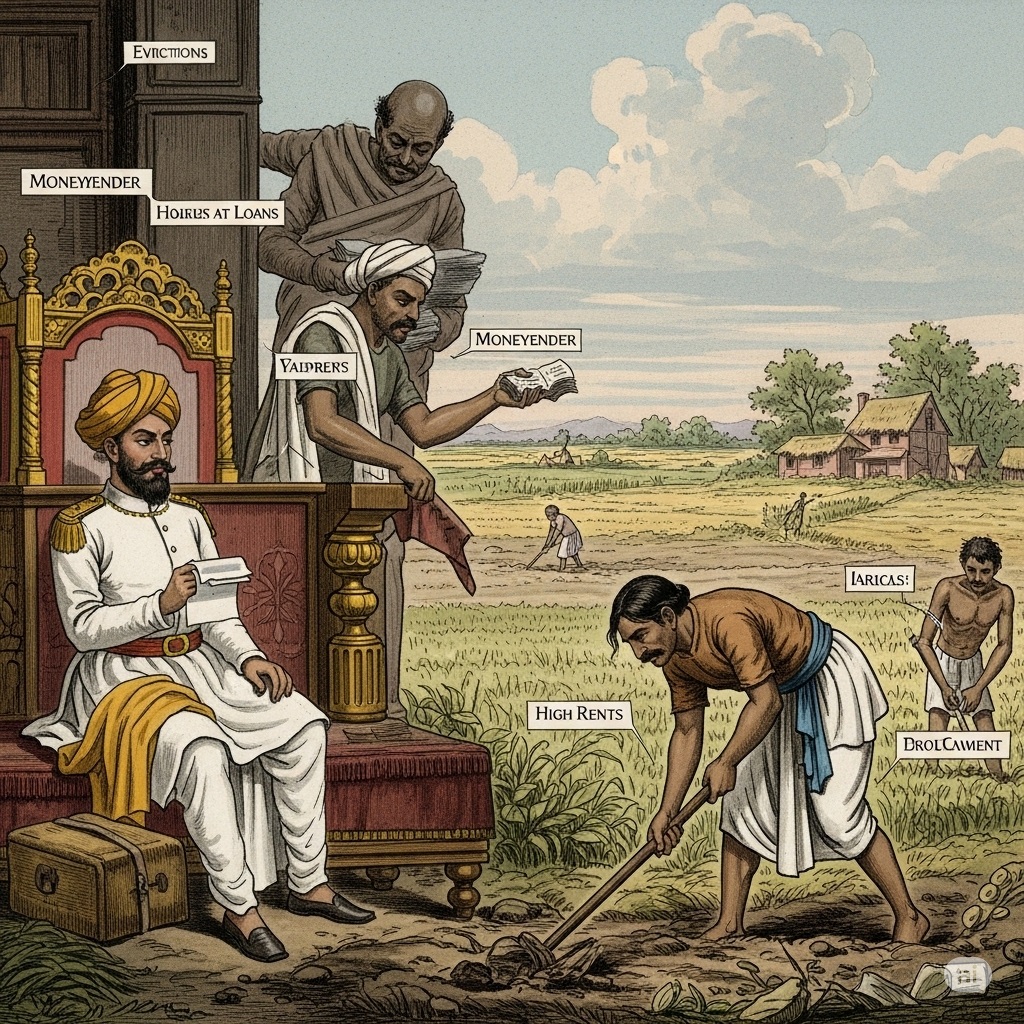

On the other hand, in the villages, the cultivator found the system extremely oppressive. The rent the farmers paid to the zamindars was high, and their rights on the land were insecure. To pay the rent, the farmer often takes a loan from the moneylender.

When the farmer failed to pay the rent, the farmer was evicted from the land where he had cultivated for generations.

A new system is devised

By the early 19th century, the company officials were convinced that the system of revenue had to be changed again. How could revenues be fixed permanently at a time when the company needed more money to meet its expenses of administration and trade?

In the North Western provinces of the Bengal presidency (mostly now Uttar Pradesh), an Englishman called Holt Mackenzie devised the new system, which came into effect in 1822. Mackenzie felt that the village was an important social institution in north Indian society and needed to be preserved. Under his direction, collectors went from village to village, inspecting the land, measuring the fields, and recording the customs and rights of different groups.

The estimated revenue of each plot within a village was added up to calculate the revenue that each village (Mahal) had to pay. This demand was to be revised periodically, not permanently fixed. The charge of collecting the revenue and paying it to the company was given to the village headman, rather than the zamindar. This system is known as the Mahalwari settlement.

Mahalwari System or Communal System of Farming

The ownership of the land was maintained by the collective body, usually the villagers who served as a unit of management known as Bhaichara or with Mahals, which were groups of villages.

Hence, the system came to be known as the Mahalwari settlement. They distributed land among the peasants and collected revenue from them, and paid it to the government. It was extended to Punjab and Madhya Pradesh.

Main features of the Mahalwari System

- The village land, including forest land, pastures, etc, belonged jointly to the village community, which was responsible for the payment of land revenue.

- Any cultivator who occupied a holding continuously for 12 years was deemed to possess permanent and heritable rights in it, subject to the payment of a judicially fixed rent.

Effects of the Mahalwari System

- Due to high land revenue demand from the government, large areas of land began to pass into the hands of moneylenders and merchants, who evicted the old cultivating proprietors or reduced them to tenants at will.

- There was impoverishment and widespread dispossessions among the cultivating communities of North India in the 1830s and 1840s, which got expressed in popular uprisings in 1857.

Ryotwari System or the Owner-Cultivator System or Munro System

In the British territories in the south, there was a similar move away from the idea of Permanent Settlement. The new system devised is known as Ryotwar (or Ryotwari). It was tried on a small scale by “Captain Alexander Read” in some of the areas that were taken over by the company after the wars with Tipu Sultan. Subsequently developed by Thomas Munro, this system was gradually extended all over South India.

The Ryotwari System was initially introduced in Tamil Nadu and extended to Maharashtra, Gujarat, Assam, Coorg, East Punjab, and Madhya Pradesh.

Read and Munro felt that in the south, there were no traditional zamindars. The settlement, they argued, had to be made directly with the cultivators (Ryots), who had tilled the land for generations. The Ryots’ fields had to be carefully and separately surveyed before the revenue assessment was made.

Munro thought that the British should act as paternal father figures, protecting the ryots under their charge.

Under this system, ownership rights to the use and control of land were held by the tiller himself. The was a direct relationship between the owner of the land and the government. This system was the least oppressive system before Independence.

Under this system, the farmer was recognised as the owner of the land as long as he paid the land revenue. The revenue was fixed for a maximum period of 30 years, depending on the quality of the soil and value of the crop.

The government collected fifty per cent (50%) of the net value of the crop as revenue.

Failure of Munro System

Within a few years after the new system was imposed, it was clear that all was not well with them. Driven by the desire to increase the income from land, revenue officials fixed too high a revenue demand. After the reforms of the Ryotwari system in Bombay (1836) and Madras (1858), which reduced the land revenue and gave land a saleable value, moneylenders began to seize the lands of their peasant debtors.

Also, the Ryot had to pay revenue even when his produce was partially or wholly destroyed by natural calamities such as drought or floods. Peasants were unable to pay, ryots fled the countryside, and villages became deserted in many regions.

Optimistic officials had imagined that the new systems would transform the peasants into rich, enterprising farmers, but this did not happen.

Land Reforms

It is policy-induced changes relating to the ownership, tenancy, and management of land. Land reforms were primarily meant for the rural areas.

The objective of Land Reforms is as follows:

Restructuring of agrarian relations to achieve egalitarian social structure, Elimination of exploitation in land relations, actualisation of the goal of ‘land to the tiller’, Improvement of socio-economic conditions of the rural poor by widening their land base.

Increasing agricultural production and productivity, Providing land-based development for the rural poor, Infusion a greater measure of equality in local institutions.

Land reform measures in India after Independence

The land reforms programme in India has been done through three methods:

- Voluntary adoption is facilitated by incentives provided by the state through measures like cooperative farming and consolidation of holdings.

- Voluntary adoption supplemented by statutory compulsion made possible by the use of legislation, as in the case of the consolidation of holdings.

- Compulsion exercised through different legislative measures as the abolition of intermediaries, tenancy reforms, the ceiling on holdings, etc.

Land Reforms and Agriculture in India After Independence

At the time of independence, the land tenure system was characterised by intermediaries called zamindars, jagirdars, who merely collected rent from the actual tillers of the soil without contributing towards improvements on the farm.

The productivity of the agricultural sector forced India to import food from the USA. Equity in agriculture called for land reforms and agriculture in India, which primarily referred to changes in the ownership of landholdings. Just a year after independence, steps were taken to abolish intermediaries and to make the tillers the owners of land.

The idea behind this move was that ownership of land would give incentives to the tillers to invest in improving, provided sufficient capital was made available to them.

Land Ceiling

The land ceiling was another policy to promote equity in the agricultural sector. This means fixing the maximum size of land which would could be owned by an individual. The purpose of land ceilings was to reduce the concentration of land ownership in a few hands.

The abolition of intermediaries meant that some 200 lakh tenants came into direct contact with the government, and they were thus freed from being exploited by Zamindars. The ownership conferred on tenants gave them the incentive to increase output, and this contributed to growth in agriculture.

However, the goal of equity was not fully served by the abolition of intermediaries. In some areas, the former zamindars continued to own large areas of land by making use of some loopholes in the legislation.

There were cases where tenants were evicted, and the landowners claimed to be self-cultivators, claiming ownership of the land. Even when the tillers got ownership of land, the poorest of the agricultural labourers, such as sharecroppers and landless labourers, did not benefit from land reforms.

Green Revolution

At the time of India’s independence, a large majority of the population (about 75%) relied on agriculture, but the sector suffered from low productivity due to outdated technology and a lack of infrastructure. Agriculture was heavily dependent on the monsoons, and without irrigation, farmers were vulnerable to crop failures.

The Green Revolution, which began in the mid-1960s, was a turning point in land reforms and agriculture in India. It dramatically increased food grain production, particularly of wheat and rice, through the use of High-Yielding Variety (HYV) seeds. These seeds required specific inputs like fertilisers, pesticides, and a consistent water supply.

Phases and Impact:

- Phase 1 (mid-1960s to mid-1970s): The HYV technology was primarily adopted in affluent states like Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, as only wealthy farmers could afford the necessary inputs. The benefits were mainly seen in wheat-growing regions.

- Phase 2 (mid-1970s to mid-1980s): The technology spread to more states and benefited a wider variety of crops.

Key Achievements:

- Self-Sufficiency: The Green Revolution made India self-sufficient in food grains, ending its reliance on other nations for food.

- Marketed Surplus: A significant portion of the increased produce, known as the marketed surplus, was sold in the market. This helped lower the price of food grains, benefiting low-income families who spend a large part of their income on food.

- Food Security: The government was able to build up a stock of food grains, which could be used during times of food shortages.

Challenges and Government Intervention:

Initially, there were concerns that the Green Revolution would widen the gap between rich and poor farmers, as only large-scale farmers could afford the new technology. HYV crops were also more vulnerable to pests, posing a major risk to small farmers.

However, the government stepped in to mitigate these risks. It provided low-interest loans and subsidised fertilisers to ensure that small farmers could also access the necessary inputs. Additionally, government-established research institutes helped reduce the risk of crop loss from pests.

Ultimately, these government actions ensured that the Green Revolution benefited both small and large farmers, proving that the new technology would have only favoured the wealthy if the state had not played such a crucial role.

Conclusion

The history of land tenure in the pre-independence era is often considered as an exploitative one, such as the Zamindari system, to the short-lived Mahalwari and Ryotwari systems. The British era of land tenure system was designed to fill the coffers of the East India Company, which created immense suffering leading to famines, debt and widespread dispossession.

The post-independence era brought a new vision. With the abolition of intermediaries and the implementation of land ceilings, the old exploitative structure was removed. This transformation in land reforms and agriculture in India ultimately led to the Green Revolution and enabled India to achieve food self-sufficiency.